This history lesson is based on Ron’s presentation to Yilgarn Retrospective, a two-day seminar presented by AIG and Geoscientists’ Symposia on March 30, 2015.

Heroic Misadventures, my last book, was subtitled ‘Australia: Four Decades – Full Circle’ as I was concerned then (in 2009) that: “These gains are possibly being squandered as we reach the end of the first decade of century 21.” Heroic Misadventures proceeded to build the case for my concerns which may have not been obvious in 2009 however, with the passing of another six years and the advantage of hindsight, it is now obvious to all.

So when I received an invitation to speak alongside a group of interesting, well-informed ‘participatory observers’, for a ‘retrospective analysis’ on the significance of and lessons learned over the past 50 years and, more particularly, of how to make these experiences useful for the future, I enthusiastically accepted the invitation. Now, for anyone who suspects that I’m simply doing another book launch as a way of selling my previous books, let me assure that this is not the case! That is despite Professor Geoffrey Blainey stating: “there is a nugget on every page”.

No, my comments are fresh recollections and there are plenty more ready to be set free! The only similarity is that Heroic Misadventures also started out as a 40-year odyssey of self-examination to see where I had gone off the rails but turned out to be more an examination of Australia, as a nation, and its own, similar derailments from time to time. (Hence the book’s sub-title—Australia: Four Decades – Full Circle—which captured my conclusion that we had pretty much come full circle and wasted several booms).

So, whilst this is essentially a personal outpouring of how the dramatic effects of the last 50 years affected my life, it is more of an overview of Australia’s exploration and mining industry over this same period. Our lives over this period have been inseparable from the fortunes of our industry and the ways in which it has taken shape, blossomed and, let’s face it, found itself dashed upon the rocks, shipwrecked and friendless from time to time. To many of us, this history of the past 50 years is like a persistent shadow, it just keeps following us around. The story that I’ll tell you is a tale of triumph and tragedy and I’ll finish with this question: “Well, what are we going to do with all our accumulated wisdom as we look forward from 2015?”

If you don’t see any reason for me to use a word like ‘tragedy’ to describe our industry, I will argue that there is no other word that expresses my feelings as I have seen our industry lose its Comparative Advantage over this 50-year period. It is a double tragedy because we have done this to ourselves, often with the best of intentions.

So let me give you a road map of where we’ll go in this probing adventure.

- How Australia was as boring as batshit in the 1950s, leading up to being ‘king hit’ by the Menzies Government’s Credit Squeeze of 1961–62.

- The nickel discovery, which came upon us slowly at first, then gathered pace as we rode the wave!

- My personal story as ‘captain’ of several small companies as I piloted them through very stormy seas.

- A question: Where were our leaders and philosophers, when we had a chance to set some sensible rules on how the game should be played? Or, how we lost our comparative advantage.

- Our own useful investment in the future. What are we going to do with all our wisdom and data?

The boring 1950s

Just in case any of you don’t realize the significance of what you were doing back there in the 50s/60s, I’ll tell you how boring, my own home town, Kalgoorlie was before you explorationists actually kicked a few goals. Following secondary school I tried to sign up for geology at the Kalgoorlie School of Mines, but the director of the school R.A. (Hobby) Hobson said, “Ron, mining has finished, so it would be far better for you to do something more involved with engineering.”

I had always been passionate about anything electrical, so I became an electrical engineer. I sat through several years of those 7pm – 10pm lectures, five nights per week, with only one finishing hour per week at the Palace Hotel. My classroom colleagues, battling away in similar fashion, were an interesting bunch of rugged individuals. Among them, Keith Parry and John Oliver, both of whom played a major part in my life journey.

There was a wide range of age groupings at the school then, as all of us had day jobs. My day job was in our family mining engineering business. (We celebrate our 120th anniversary of doing business this year and I must say right now that I’m enjoying the third time in my life when I feel that I have got it just about right with team spirit and performance). The electrical engineering choice turned out to be fortuitous, as our family company was struggling (just as the whole region was struggling under a government-imposed fixed price of gold, $35 per ounce, for many years). We survived by converting the Goldfield Region’s steam-driven mine winders to electric, featuring very sophisticated electrical systems of over-speed and overwind protection, a major improvement from the earlier steam-driven winders.

However, this came to an end, like so many jobs today, doomed to extinction and we moved into a demoralizing period when shafts were being closed, almost on a monthly basis, and in many cases the winders and headframes were being disassembled and shipped off overseas. I recall that some went to Brazil. Our business was barely viable, so my father and I bought a small farm at Esperance where we took turns to run sheep for a couple of days a week and then serviced the Norseman mining area through a small branch in the main street while still managing our business in Kalgoorlie, backed up by excellent staff. Most of my school friends had managed to escape from Kalgoorlie and head for greener pastures. In the hope that Australian mining would see a resurgence of gold mining, some of the remaining remnants, still left in Kalgoorlie, attended the occasional prospector lectures. I remember one by Sam Cash on ‘Loaming for Gold’. These notes I referred to several years later.

Gold mining or prospecting was hard to imagine as something that would ever provide one with a livelihood, but the historic romance of it all maintained our interest. So, that was the backdrop when disaster actually struck, in the shape of the Menzies Government’s Credit Squeeze in 1961–62, when by one simple edict they instructed the banks to reduce all business overdraft limits by 50 per cent. The government’s motivation was that they saw signs of prosperity so they needed to rein it in.

Perhaps this was about the time that I started developing a strong sense of cynicism toward all government actions and began suspecting that the end results of their activities were often the opposite of their stated intention. The credit squeeze brought on the demise of most of Australia’s major retailers. National chains of stores such as Cox Brothers, Reid Murray, HG Palmer and Eric Andersons simply closed their doors because there were insufficient hire purchase facilities to keep going.

Most of my memories now, from the fifties, the happy ones anyway, were simply about discovering jazz, discovering girls and thinking how difficult it was to be intelligently creative in business when for so much effort you actually had so little to show for it. Well, with all that boredom, along with a government-fixed gold price of US$35, what else could go wrong? The whole region was desperately in need of a visit from the proverbial ‘tooth fairy’.

The new nickel era started slowly…

The ‘tooth fairy’ arrived in the form of an exploration revolution. The revolution was started by Roy Woodall and his merry team at Western Mining Corporation. There were stirrings around the Goldfields that something was about to happen. I remember, in late 1965, that an important figure in the State business community (it may have been the Chairman of Wesfarmers) wrote to my father and said, “Charlie, I’m hearing good things about Western Mining Corp, what sort of a company are they?”

I was with my father when he was reading the letter and recall him giving me some advice on what to do when people ask for opinions in this way. His first comment was, “gather the facts”. So, we both walked across the road to Ron Reed’s office (Kalgoorlie stockbrokers) and obtained a copy of Western Mining’s latest report and I recall my father replying along these lines: “From the balance sheet they look as though they are going broke, but the people are sound and they know what they are doing.”

A few months later, Dad and I were in Perth at a function and this same correspondent marched up to Dad and said: “Thanks Charlie for your advice, that investment has turned out well for me.” Dad replied: “I thought I may have put you off with my concern about their balance sheet?” I can clearly remember the gentleman replying: “From my experience, in Western Australia, balance sheets don’t count for much—it’s all about the people.” I often think about that comment whenever I’m doing business with anyone and it has worked out well for me.

There were two distinct phases to Western Australia’s appropriately named nickel boom. Some people object to the name ‘nickel boom’ but it totally transformed the sleepy back blocks of our state, with overflow effects on the entire nation. The world took notice and started to arrive in plane loads. Anyone who could string a few words together became an interviewable celebrity. Kalgoorlie went from having a few remnant geologists to having the highest number of geologists of any city in the world, with New York City running second. 350 exploration companies beat a path to our Goldfields area motivated by the fear of missing out. How many of those 350 actually made a profit? Two — Western Mining Corp and Metals Exploration at Nepean.

I say there were two distinct phases to the boom, the first being the Western Mining, Kambalda discovery. This discovery did not amaze people, as it was seen to be done by a group of highly professional technologists who had been beavering away for many years and had accumulated patience and skills. They had confidence in themselves and the community had confidence in them. That community confidence probably held the region together during all those difficult years.

Then, there was the Poseidon nickel boom three years later. This discovery appeared to be made by a 2-cent company run by Norm Shierlaw, an Adelaide stockbroker, who no-one had heard of. They had seemingly driven a drill rig a few kilometres out from Laverton, dropped a few holes and discovered what was thought to be another Kambalda world-class nickel region. This looked to have been achieved without much technical input and that’s when the proverbial shit hit the fan.

All those companies, now based around Kalgoorlie, searching for nickel came under intense pressure from management and boards. The refrain was ‘if this little two bit company can do it, then so must we’. Exploration budgets were doubled and the media attention immediately quadrupled. How I lived through those next few years I’ll never know.

Prospecting days

Suddenly my prospecting skills went from hobby status to being extremely useful as I set out to peg half the state, optimistically thinking that this would go on forever. Prospecting became an all-consuming passion for me and I was fortunate in developing a wide selection of partners who I enjoyed working with. They included some aboriginal contacts made from my earlier primary school attendance in Kalgoorlie. I learned of their skills in actually seeing subtleties in the rocks with their naked eye which our geologists appeared only to see with the assistance of magnifying glasses or microscopes.

So, I equipped several of them with old wooden cigar boxes, suitably partitioned, containing a range of nickel gossan samples, to give them an idea of what we were seeking in our search for nickel prospects. This resulted in a degree of success and if, after a first-pass inspection of the ground there was some significance in their gossan discovery, I paid them a flat fee of $10,000. At that point of minor encouragement I brought in one of the local geologists. I would hire people such as George Compton, to do some of the reconnaissance work. If the interest was maintained, the ground was then pegged. If there was insufficient merit, then it wasn’t pegged. The aboriginal prospectors received their $10,000 and I took my chances. Such is the nature of entrepreneurship.

Probably my favourite prospecting partners were John Henry Elkington and his wife, Norma. John had commenced geological studies but diverted himself into prospecting as a way of leapfrogging, as it were, his geologist brother, Dick Elkington. He desperately wanted to find a mine before his brother did. John and I acquired many significant areas over the years and this led to a series of corporate adventures. Our prospecting company was aptly named Mannelksploration Pty Ltd. We had developed an affinity for the Forrestania area and were actively involved in securing some strategic ground there when the state government announced a ‘pegging ban’. Can you imagine that? In the middle of a full-scale nickel boom their registration bureaucracy fell behind in their record keeping, so instead of speeding up their own process and solving their deficiency they instead announced a ‘pegging ban’.

Well that brought to a halt the momentum that had been building up and all we could do was continue prospecting and ‘sit on’ the results until such time as the ‘pegging ban’ was repealed. The state government gave notice that on a certain day they would be making an announcement over the ABC shortwave band that the pegging ban had come to an end. There were whole battalions of prospectors and geologists all stationed out on their special prospects which they had been working on, during the time of the ban, waiting for the ‘blips’ to come over the radio and at that moment it was on for young and old. Fortunately, Mannelksploration acquired some prime ground at Forrestania which is still being actively explored/mined. Preliminary work was done there by our joint venture partners, AMAX Inc, the major US mining company.

We successfully prospected the Forrestania region for some years, resulting in pegging the Maggie Hays Hill (later the basis of the successful floatation of the public company Theseus Exploration NL. Incidentally, history tells us that Theseus was the illegitimate son of Poseidon). From Maggie Hays Hill we then continued working down the Bremer Range formation from the north, finding this geological environment fascinating. Everything else was covered with sand.

I was reminded about a certain incident several weeks ago, at well-known geologist Ed Eshuys 70th birthday party, when Ed related the following story, that stirred my memory. Ed, at the time, was the manager for the Belgian Government’s exploration arm, Union Minière were also wildly enthusiastic about the Bremer Range region and frantically and they prospecting and pegging up from the south. They had a substantial team, by far out-stripping our humble DIY team and they were, with great speed, digging the prescribed trenches and hammering in the required pegs (of those days). They were certainly working with great speed but, being typical government employees, right on the dot of 4pm they promptly packed up and headed back to camp.

You can imagine the sheer delight and ecstasy that we experienced when working down from the north we came across all these ready-dug trenches with the tenements all marked out and pegs all in place but, of course, no papers were fixed. Being of an extremely tidy temperament we felt that no job should remain incomplete while the sun was still shining, so we continued merrily papering all these delightfully positioned pegs. Our enthusiasm was so great, in fact, that we worked well past midnight, by kerosene lantern, to ensure that our task was completed. Actually there was added job satisfaction for us as we lurked in the bushes and witnessed the absolute cries of anguish from the Union Minière team when they arrived the next morning.

However, it wasn’t long before we, Mannelksploration Pty Ltd, received a summons to appear in the Norseman Warden’s Court, accused of having performed something of a dastardly act. John Elkington and I had Kalgoorlie Solicitor, Tom Hartrey – the well known political orator – defending us on this occasion and, as usual, his courtroom performance was spell-binding. There was always excitement when crowds gathered to witness Tom’s eloquence at its best. He proceeded to assure the magistrate that this situation ranked far above the humble Warden’s Court and in fact was a matter of ‘international natural justice’. Union Minière had been downright careless; he likened them to a careless fruit tree owner who deliberately grew ripe fruit over his boundary for the benefit of all those passing by. Neither the Warden nor Union Minière’s attending solicitor were up to this full frontal confrontation by Tom Hartrey and we walked away with the prize.

Naturally we celebrated well into the night and this secured ground became the basis for the public float of Kalmin Exploration Ltd which we did not realize at the time was the last company floated out of the nickel boom. The hysterical aspects of the boom really only lasted for about 18 months then collapsed with heavy breathing and gurgling shortly thereafter. (Kalmin Exploration Ltd then transformed itself into Bellcrest Holdings Ltd which became one of W.A.’s active home builders but more importantly Ed Eshuys has forgiven me for this ‘pegging mischief’ and we remain firm friends to this day.)

The first ground I ever pegged was at Siberia (north of Kalgoorlie) and it went into a new float called Westralian Nickel NL. They soon appeared to have found another Poseidon/Windarra, causing their shares to rocket to $8.80 and I copped a big fat tax bill based on that figure (accurate at June 30 of that year). However, my shares were escrowed and unsalable. I ended up selling them at 15 cents each the following year.

The Australian Taxation Office showed little interest in my predicament, so realizing that they had no comprehension of natural justice, I simply had to leave the country as they were repeatedly sending me interest bills on the large outstanding amount. I kept busy overseas with several jobs, such as running a hotel in Bali and working for an up- and-coming merchant bank called Nugan Hand. Nugan Hand’s specialty was money laundering, a very useful and noble enterprise at that time. We kept busy with a range of clients including the Reagan Administration and its involvement in the Contras’ activities in Nicaragua. An interesting career for a young prospector from Kalgoorlie!

However, all that came to an end when the managing director of the bank was murdered on Australia Day in 1980. He had his head blown off. Up until then I had often felt that the excitement of merchant banking beat the hell out of converting steam-driven mine winders to electric, back in Kalgoorlie. However, once again, like converting steam driven mine winders, my position was declared redundant. I then made peace with the Taxation Office. They tore up my files and I once again returned to the Australian workforce. That timing was fairly good as gold had suddenly stuck its head up, peaking at US$860 in January 1980, as a result of the oil crisis and the Middle East OPEC members who were desperate to pump their surplus funds into anything real, such as gold, as they were becoming increasingly alarmed at the future of the US dollar.

So, let’s take a break from the personal reminiscences for a moment and look back at this tumultuous period of our state’s exploration history. To illustrate the difference between what I call the two booms, let’s look at the way both were celebrated in retrospect (always a more accurate view of history; looking back).

Kambalda Nickel 25th anniversary event

On September 15, 1992, Western Mining Corporation staged a 25th anniversary event for its senior staff to reflect on the significance and the very substantial outcome of the Kambalda discovery. That was the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Kambalda nickel mine by the then State Premier, the Hon. David Brand. It was my good fortune that my wife, Jenny, and I were invited to these celebrations. As someone once mentioned, although I had never worked for Western Mining, I always ‘seemed to be there’.

John Oliver, my earlier School of Mines colleague, and I continued a strong friendship and I clearly recall, one Saturday afternoon in 1966, he telephoned me and said: “Come on Manners, let’s get out to Kambalda. We have some important decisions to make.” The ‘we’ was Western Mining Corp. As John was the Resident Manager, he drove out to a very unimpressive sheep watering trough at Kambalda and the two of us walked up the side of a hill overlooking the lake. John said: “We have to start mining quickly here otherwise we will lose this nickel market opportunity. We haven’t done enough drilling to properly decide where we should sink the shaft, so how about we simply sink it here because at least it has a good view of the lake?”

My vote didn’t really count, but I agreed. John then said: “What colour is the lake?” I said, “It really wasn’t a colour it was just simply silver.”

“Okay, let’s call it the Silver Lake Shaft,” John said.

That’s how decisions were made in those days before our industry became infested with committees. That’s when managers were allowed to manage. John was pretty good at making decisions and I think he had named all the Kambalda streets before a Town Planning Committee was formed too. Again, that’s the way decisions were made in those days before our industry surrendered to the various branches of bureaucracy.

Just look at this achievement timeline for the Kambalda operations:

- January 28, 1966 — massive nickel sulphides were intersected at Kambalda.

- February 21, 1966 — the discovery was announced to the Australian Stock Exchange.

- April 4, 1966 — WM Morgan, Western Mining’s MD, announced a ‘significant’ discovery at Kambalda.

- April 7, 1966 — announcement that ‘under-ground development’ would begin.

The key significant figure, of course, is that from the discovery hole until concentrates were produced was only 17 months. Just try achieving that today!

Yes, there was a lot to celebrate at the 25th anniversary. There, at that anniversary, they were celebrating a 100 per cent-owned productive asset, brought from discovery to production in record time by real leaders. Those were the days when miners were heroes, enthusiastically supported by communities, politicians and regulators, before the rot set inii.

The Poseidon 20th anniversary

I know about Poseidon’s 20th reunion because I organized it. Early in 1990 I had an idea. Should we allow the 20th anniversary of the Poseidon boom (the stock market peak of the Poseidon shares) to pass without a celebration of some kind? I felt we should gather together about 15 of the original Poseidon participants as it would guarantee a good night of reminiscences at Kalgoorlie’s Hannan’s Club. So, out went 15 ‘faxed’ invitations. Instantaneously I received 52 acceptances, as the invitations had been passed on.

It resulted in a great night at the Hannan’s Club, a star-studded evening of good humour, where, at last, many true stories of those times were revealed. In attendance were Norm Shierlaw, other Poseidon former directors and an incredible supporting cast. The event was ably reported by Ross Louthean and Trevor Sykes whose stories were incorporated into a commemorative souvenir and it formed an airline magazine article, both of which were reproduced in my Heroic Misadventures bookiii.

Here is the photograph of the assembled gathering, as it appeared in the airline magazine. The event was in complete contrast to the Western Mining Kambalda event, but nevertheless significant in its own way.

Australia’s great gold renaissance 1980-2002

The nickel industry had quite a few tough years, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, although our family company kept busy by introducing some productive tools, particularly in the form of the Wagner Scooptram diesel loaders from US and Kiruna low profile underground trucks that we were importing from Sweden. Then the region experienced a new dimension when gold started sending out a few green shoots following President Nixon’s breaking of the link between gold and the US dollar, in 1971.

As I mentioned earlier, gold really got some wind into its sails with the massive investment from the Middle East oil producers turning their surplus cash into gold. This brought on a whole range of new listed companies. There was a huge difference in this generation of ‘gold’ companies compared with the earlier listed ‘nickel’ companies, for two main reasons. One was to do with the tax implications. With nickel, there was a tax penalty for being on the board of your company, however, with gold it was acceptable, so that’s when we all became very ‘hands on’. The second was that there was now an abundance of skilled technical and corporate people to go on to boards (in complete contrast to the earlier nickel companies).

Among the companies that developed some substance were Metana Minerals, Sons of Gwalia, Delta Gold Ltd, Normandy, Great Central NL and Croesus Mining NL. I’d like to mention a few highlights and lowlights of my time with Croesus Mining as I’m certainly more familiar with that company, although, I was also a founding director of Great Central Mines NL.

Croesus Mining NL — highs and lows

I do cover the 20-year lifespan of Croesus Mining in my Heroic Misadventures book, so I’ll only touch on a few points here. My other old School of Mines colleague, Keith Parry, often mentioned to me in the early 1980s that I should stop joint venturing my mining properties out to other companies and actually “form your own company to do all the exploration yourselves and if you get the right people together you could be just like Western Mining Corporation before we lost our way.” Well, I did register Croesus Mining NL in 1982 and we were ready to move toward listing with some extensive properties at Polar Bear Peninsular near Norseman and just about all the Mount Monger Goldfield included.

Well-known mining solicitor, Chris Lalor, agreed to be the Chairman. We were moving toward listing when a former non-performing joint venture partner, White Industries Ltd, announced that they intended to exercise their ‘pre-emptive right’ over the property because once they knew what we were doing with it, they thought they should do the same and they were moving toward putting the property into their own float, AUR NL. I had several robust phone discussions with Travers Duncan (White Industries) where I politely mentioned to them that they had relinquished their interest and had never had a ‘pre-emptive right’. However, they responded that they had their own in-house solicitors and they had more money than me and, from this, I knew that resolution would probably be some time away. So I moved the Mount Monger areas into another public company called Mistral Mines NL and became its Exploration Director, until such time as I had gathered together the replacement ‘land package’ for Croesus Mining.

This took until late 1985 and by that time Chris Lalor was thoroughly occupied with his new role in Sons of Gwalia and I replaced him – albeit as Executive Chairman. We listed in July 1986, the only company to float in that miserable year, with three well- known brokerage houses backing the float. Just for interest let me mention who they were:

- TC Coombs of London as underwriters

- May & Mellor, leading Melbourne stockbrokers

- Ray Porter & Partners from the Perth Stock Exchange (which was quite separate to the other Australian Stock Exchanges at that time).

It’s interesting to reflect that none of these names exist today – an illustration of how volatile many aspects of our industry have been and will remain. We raised $2m which we promptly spent on enthusiastic exploration which, to our disappointment, produced no mineable deposits anywhere. At that point I realized the need for a cash flow (after many years in business I knew the importance of cash flow). I saw an opportunity when CRA (Rio Tinto) announced that their Goldfields Region prospects were all for sale as they had decided to move out of gold. I saw this as a great opportunity for Croesus and promptly headed to Perth for CRA’s head office to ensure that we were on the tender list. They and their advising bankers would not include us as we ‘had no credit rating’.

So, I walked up the Terrace to Westpac Bank and explained that we could not get on the tender list without a Letter of Credit from Westpac. Westpac, realistically, explained why they had some difficulty in issuing a company, who had just run out of money, with a Letter of Credit.

With tongue in cheek I asked how much they would charge to actually lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. They hurriedly had a meeting in the next room where they probably had a good chuckle and returned to advise that they would charge me $25,000 to lend me a Letter of Credit until noon the next day. That’s all I needed. The next morning I marched up to CRA’s office proudly displaying this document and was consequently included on the tender list. They alarmed me by wishing to keep the Letter of Credit and I explained that it was mine and not theirs, but they should feel free to keep a photocopy of it. They found this to be satisfactory and I managed to get the Letter of Credit back to Westpac at one minute to noon!

Our tender offer for the CRA areas was $20.3m or 2.5 per cent higher than the highest bid, whichever was the higher figure. They pointed out that this was a non-conforming bid but I managed to convince their banking advisors that their prime responsibility was to obtain the highest figure possible for their clients, and on that basis they should honour that commitment. At the conclusion of the tendering process we walked away with that prize which, in my mind, mainly consisted of the Hannan South Mine.

There is quite a story on how we managed to pay the 10% deposit by 10.00 a.m. the morning after winning the tender and finance the entire purchase within the 21-day prescribed period and managed to repay all the loans from gold production within nine months. With much help from an enthusiastic board, staff and well chosen consultants, with special mention of John B Oliver and HM (Harry) Kitson, Croesus Mining NL embarked on a productive and profitable 20 year adventure where we mined 25 open pit and two underground gold mines and paid 11 dividends to our supportive shareholders.

Croesus Mining — Gold Company of the Year

The ill-advised so-called Native Title Act came into being as we were developing the Binduli mining area just south-west of Kalgoorlie and we ended up with eight competing claimants over that area at a time when we were all ready to build a new mill and feed it from several open pits. The eight claimants were basically all members of the same family and I could already see the nonsensical frustration that lay ahead of our industry.

Our mill never got built. The plans are still in plan cabinets so to stay in business we high- graded the mine and trucked the ore to our Hannan South Gold Operations. I estimate that Native Title delays cost Croesus Mining $26m and that, to us, was a lot of money. The money didn’t go to anyone, it was just that the gold was never produced. I was not enjoying these non-mining frustrations that were encroaching on our industry and at that point decided to sell my interest in Croesus Mining.

An interesting process emerged to find the most suitable incoming major controlling shareholder and our advisors had identified eight suitable companies. This was a most interesting and complex procedure but one that I would recommend to any major shareholder planning to depart a public company. Somewhat similar to planning your own corporate funeral.

The Winning Team — 1995

I brought senior staff into my confidence throughout this entire process and I was asked what I would do if I found that the best offer, to guarantee the future of the company and the fantastic team we had put together, was not found to be the same offer that gave me the highest dollar amount. This, in fact, was the case and it actually cost me a quarter of a million dollars, but I felt the outcome was worthwhile. The incoming Canadian company, Eldorado Gold, were really acquiring a first-class technical team that they wished to deploy to Indonesia and participate in some new generation discoveries, i.e. Bre-X.

Part of my contract with the incoming Eldorado Gold was that I would go on their Board and would cease being Croesus Executive Chairman within six months of the transaction and leave the company within two years. The events that unfolded made this extremely difficult. However, I had already moved out of Kalgoorlie to Perth and reactivated my family company which for several years been capably operated by my co-director, Harry M Kitson.

The eleventh and last dividend that Croesus paid was rammed through by me, much to the protests of senior staff. I felt, at that stage, that the cash would be more usefully utilized by the shareholders rather than left at the disposal of the new crop of executives. Following a series of tragedies, Norseman death, gold stealing charge and a decline in respect and mutual trust.

Corporate decay (the second sign)

Shortly after that I resigned as Chairman and quite a few months later a most efficient and effective period of administration was facilitated by Pitcher Partners who cleaned the company up, appointed a new Board with new properties and proceeded to turn it into something of an example of how intelligent exploration can create a new future for old companies and give former shareholders something to smile about. Well one of the properties maintained through this entire era was the original Polar Bear tenements and I’ll just mention this because, again, it shows how patience can pay off.

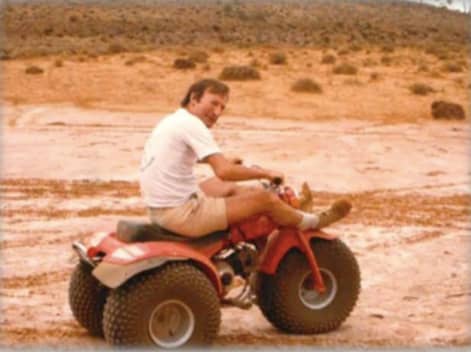

Caption: Ron, 1979. Pegging Polar Bear (Sirius – Taipan).

Caption: Ron, 1979. Pegging Polar Bear (Sirius – Taipan).

In 1979 I was drawn to the area because of the early 1970s exploration by the US company, Anaconda Inc, which was then run by geologist Tony Hall, who later became a director of Croesus Mining NL. Further exploration was later conducted by another U.S. company, Duval Mining. My files show that following my pegging as Mannkal Mining Pty Ltd, the ground has passed through a series of companies’ hands, including:

- Terrex Resources

- White Industries

- A.U.R. Ltd

- Mareeba Mining

- Thames Mining

- Dominion Mining.

I suspect there were several others, but after some timid exploration the ground came back to meand then it found its way into the Croesus Prospectus in 1985. Croesus became Sirius Resources NL and now, 36 years after my original pegging, someone actually had the courage to drill a hole and bingo!!! Or, as geological writer, Keith Goode, says in his report: “Sirius hit the jackpot.”Again courage and imagination is reactivating our Australian exploration industry. Patience and perseverance have prevailed. Congratulations to Mark Bennett and his team at Sirius Resources.

How we lost our comparative advantage

Question: Where were our leaders and philosophers, when we had a chance to set some sensible rules on how the game should be played?

1969 Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson was once challenged by the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam to “name me one proposition in all of the social sciences which is both true and non-trivial.” It was several years later that he thought of the correct response: comparative advantage:

“That it is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that it is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them.”

I humbly suspect that our mining industry’s bright and intelligent people were among those who didn’t appreciate this concept of comparative advantage, otherwise they would have resisted repeated successful attempts by various enemies of our industry to de-knacker it. This has led to a decline from hero status to ‘pathetic performance status’, where investment returns are such that no-one in their right mind would rely on dividend flow from our resource companies to finance their future. If what I’m saying is true, then this reflects badly on our industry leadership.

Talking about the word leadership, our Mannkal Foundation ran an essay context last year at Curtin WA School of Mines. The contest challenged students to search for leadership in our industry and report on any examples they could find. There were 35 finalists in the contest. Overall it confirmed that, apart from the courageous few (three or four), there exists a leadership crisis in our industry…generally populated by puppets and caretakers.

The over-use of the word ‘leadership’ could lead to it becoming yet another ‘weasel’ word where any real meaning is blurred. Here are some other words and descriptions that fall into the category of weasel words:

- sustainability

- corporate social responsibility

- social justice

- global warming

- political correctness

- native title

- traditional owners, or the current push to change Australia Day to Invasion Day.

- and last, but not least, stakeholders — where companies are ranking stakeholder interests before shareholder interest (it is no wonder that investors have gone elsewhere).

All of these words or phrases have been used by various rent-seekers as weapons in their campaigns. As public choice theory economists have shown, there is a lot of money to be made by the few who benefit, while the costs are designed to be spread across such a wide number of ‘victims’ that, although debilitating, they are not ‘life threatening’. The result is that those who benefit greatly from these programs are incentivized to put in a huge effort to advance their interests, whereas the many who share the burden are not as well organized and continue to carry the financial burden.

The usefulness of public choice theory in explaining bad government (or company) policies was explained to me by John Buchanan in Moscow, September 1990 and Robert Nozick described resulting government policy:

“The illegitimate use of a state, by economic interests, for their own ends, is based upon pre-existing power of the State to enrich some at the expense of others.”

Governments and corporate executives are in fact giving away money that is simply not theirs to give. If they had any understanding of public choice theory they would realize that the moral thing to do is simply say no to all these competing demands for corporate support. Economists describe this as ‘concentrated benefits and diffused costs’. The costs are nevertheless substantial and have in many cases caused Australia to become uncompetitive. Totally unhelpful at this time of Australia’s soaring deficits.

Might I suggest that for every ‘social’ style of seminar that mining executives attend, they should attend two seminars on ‘becoming profitable’. Fortunately, the next generation is not hood-winked by this redistributionist nonsense. They are more anxious about the average debt of $85,000 that our generation has left for them to pay off (and that’s not taking into account any student loans they might have) see. It is ‘their’ money that the politicians are spending in order to be re-elected.

This ‘broken political system’ is seen clearly by the next generation and they are increasingly making their feelings obvious via their effective use of social media. While on the subject of weasel words and nonsense served up to us in the media, I recently heard that the Rudd Government had successfully steered Australia through the Global Financial Crisis by giving Australians (alive or dead) a A$900 stimulus package with which to purchase an imported flat screen TV.

Yes, that explanation was served up with a straight face. The actual truth, far removed, was that the Campbell Committee forced our Australian banks to put their houses in order (around the time of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1996) and our banks hadn’t had time to get themselves untidy again when the Global Financial Crisis hit. That’s the real story of why we survived the GFC.

When did the tide start turning against our mining industry? Perhaps some of you can remember the dark days of Gough Whitlam and Rex Connor in the mid-70s, with the mass exodus of geologists overseas. Signs on office walls displayed the message: “Will the last businessman leaving Australia please turn off the lights.” We haven’t ever recovered from that anti-development mindset. Sir Arvi Parbo concisely summed up Australia’s business environment in an interview in the October 1995 edition of Director magazine:

“Today when you do something you know that from the first day probably half of the country is working against you in some way or another. Half of the government is working against you. You will have departments in favour of what you are doing, and probably an even number of departments very much against it. They will want to hem you in and stop you from what you are doing, or at the very least, make sure that you can only do it in a restricted manner.”

That’s when the leadership of our industry should have taken up Sir Arvi’s challenge and instituted a set of rules for our industry that would have restored our comparative advantage. Now in 2015, it’s late, but not too late, to do something about it.

However, is anyone doing anything? Well, last week I saw one example and that is Gina Rinehart. She meticulously documented the 4940 approvals, permits and licences that they have so far been forced to comply with to bring in their single Hope Downs mine. This list was submitted to Premier Colin Barnett for his consideration and comment. Let’s wait anxiously for his response.

Why can’t we see more leadership like this in our industry? Where are our mining leaders when we need them? I always enjoy going through my old files and over the weekend I found some notes from a speech I gave in Toronto at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) in March, 1997, about a year after Sir Arvi Parbo made the quotation I just referred to. Amongst the things I mentioned in Canada was the reason why Australians and their money were leaving Australia. It had simply become too difficult for us to ‘get on with the job.’ I also described some differences between Australians and Canadians and generalized by saying that Australian’s take business very seriously but at the same time don’t take themselves very seriously.

Once Canadians realized that comfortable contradiction, I continued, they will understand the Australians and their peculiar sense of humour. For example, it probably explains why male Australian geologists always give their penis a name. They can’t stand the thought of their major decisions in life being made by a stranger!

Back to reality. While we are on the subject of regulations, rules and general impediments to industry, I should caution about adopting a ‘victimhood’ status for our industry. Why? Well, victims cannot be leaders. If you view yourselves as a victim in any corporate sense, or in any aspect of your own life, you are giving your power away. If you are a victim, someone else has to change to make you happy but you cannot change anyone else. For leadership to emerge from our industry, we must get up off our knees and change ourselves. It’s part of the individual responsibility package that comes with true leadership. This victimhood angle is one of the reasons why the Native Title Act fiasco has failed the aboriginal people. From their perspective it has been based entirely on the cult of victimhood.

Native title files

These extensive files go right back to the beginning of the native title fiasco. I recommend two books — Red Over Black by Geoff McDonald (1982) and The Fabrication of Aboriginal History by Keith Windschuttle. I have written much on the absurdities of the Native Title Act and in 2004, the last time I calculated native title cost of lost production to Australia was $90 billion. Just before leaving the topic of leadership, let me mention several specific examples of how we are failing:

- Last week, in Hong Kong, at the big Rugby 7s 40th Commemorative Dinner, I heard two rugby legends each speak for 40 minutes. They both spoke without notes and with great passion. I sat there wondering why our industry, the most imaginative and creative industry in the world, has failed to create a significant collection of people who can speak with similar passion about their industry?

- Last week we witnessed two political funerals (Malcolm Fraser and Lee Kuan Yew) but when our own industry legends pass away there is hardly a murmur in the media. I mentioned Norm Shierlaw as the father of the Poseidon boom. When Norm died in September 2013 I didn’t hear about it until April 2014 (six months later when I read his obituary in the AusIMM Bulletin). When Kingsgate’s Gavin Thomas died in June 2014 – apart from his company’s notice of his memorial service — there appeared to be no mention in the media. When Geoff Donaldson died in July 2013 – again, hardly a media mention. Without Geoff Donaldson there would be no Woodside Petroleum. We have lost our ability to sell our industry as an exciting, creative and profitable endeavour to the point of encouraging investors to join us in our risk-taking. Instead we now accept and solicit taxpayer funds to take on the first pass risk of exploration and this was summed up neatly by the South African mining writer, Kip Keen, who this month nominated the Western Australian Government as ‘Prospector of the Year’ as a result of taxpayers’ funds being spent on first-pass exploration for two Australian companies, Gold Road Resources and Sirius Resources. If our industry is not prepared to take the risks themselves, then they must accept the fact that the acknowledgement prizes will not go to them either.

Wisdom and Data

So, we come to the final question raised earlier…What are we going to do with all the wisdom and all that data that we have accumulated over all these wonderful 50 years? I’ll bet everyone in this room constantly receives requests for information on the very substantial areas with which you have been involved. Last week I received two such requests. One from Rohan Williams (now at Dacian Gold Ltd), the new owner of one of Croesus’ 1986 mines, Jupiter, at Laverton, and the second from Colin McIntyre, now responsible for breathing some life into Norseman.

Colin was looking for a 2003 study we completed on several open pit optimisations, including HV5B pit (on the edge of Lake Cowan), when the gold price was A$540. Now, at a current gold price of A$1500, those pits start to look robust. Never underestimate the value of your old data, as it will be treasured by those who follow. Equally important, is the need to make yourselves available to the new and important generation of explorers. If you haven’t found a home for your own data, let me encourage you to do so and do it quickly, before your descendants mistake it for garbage and send it off accordingly.

I had about 2.5 tonnes of such material and it wasn’t easy giving it away. Nobody wanted ‘the lot’, so, in 2006, after much discussion, I split it into three specific packages (they’re all about the same weight) and I’ll mention this in case it is useful guidance for you. One third, advanced prospects, that could emerge when circumstances were right, went to a young entrepreneurial mining engineer and I have the opportunity to contribute to any commercial development that may eventuate. One third went to Curtin WA School of Mines, an extensive collection of maps, aerial photos, sundry papers and reports. This was all co-ordinated by Professor Philip Maxwell, Bob Fagan, Kerry Bradford and Libero Parisotto. The remaining third then went to the Geological Survey of WA: an extensive collection of company Prospectuses and Annual Reports covering the 50 year period, along with a laptop and data-base.

You might remember that a company prospectus of that era contained considerable useful information. They contained a bibliography which listed all earlier reports and references on the ground covered by that company’s tenements. I had data-based all this company information, cross-referencing to the subject mineral, authors, companies, etc. This information was well received, because some time before that, geologist Bob Pickering, had left his collection to the Geological Survey but they had misplaced his data-base and indicated that Bob’s information could easily be included on my database.

This information handover was co-ordinated by Dr Ian Ruddock and Tim Griffin and in their acknowledging letter of April 4, 2006 they stated: “The collection will mainly be used by our Mineral Resources Group as a useful source of data for the WAMIN and MINEEX data bases on mines, deposits, prospects and occurrences within WA. It would also be made available to the public and the Library at Mineral House.” So I was then 2.5 tonnes lighter and could once again fit my car into our garage.

I hope my old data, along with your own, will guide future generations towards some exciting discoveries. Let’s finish with some good news (particularly for gold). Last Tuesday, in Hong Kong, I had lunch with Doug Casey, the noted investment commentator. Here is his useful gold graph. It indicates that the current downturn in US dollars gold price is not much different to previous percentage downturns and as we both have tremendous confidence in governments’ ability to destroy currencies there is certainly a great future for gold.

Conclusion

Friends, it has been my pleasure to join this distinguished group of active participants in this fast and furious 50 years’ retrospective. They say that all progress takes place outside the comfort zone and this is where your achievements were made. The words of the old American Indian proverb could have been written with you all in mind: “You will be known forever, by the tracks you leave.”

Thank you.